They hide on your clothes, in your car, and in your hair. When people normally find them they gasp in disgust, stomp them to death, fling them out windows, or burn them. So why, you might ask, were my stalwart companions and I seeking them out?

For science, of course!

The Battlefield is assisting the Center for Disease Control’s attempts to capture and test these obnoxious bloodsuckers for a couple different pathogens. You may already know that ticks can transmit Lyme Disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and a lifelong allergy to mammalian meat. But did you know that they also transmit about ten other diseases, like Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, and Powassan disease? The CDC website can tell you all about them, but I won’t link to it here so as not to distract my hypochondriac readers.

Unfortunately, these illnesses have become more of a concern in the recent years. Lyme disease is now listed as the US’s most common vector-born disease (meaning that insects or arachnids transmit the infectious microbes), affecting nearly 30,000 people a year. The CDC is understandably eager to better understand this pathogen.

And what do you know? The Battlefield has a multitude of ticks—perhaps more than any other National Park! So in the spirit of inter-agency collaboration (the theme of this summer) my team of natural resource conservationists scoured our forest floors in search of these vicious arachnids.

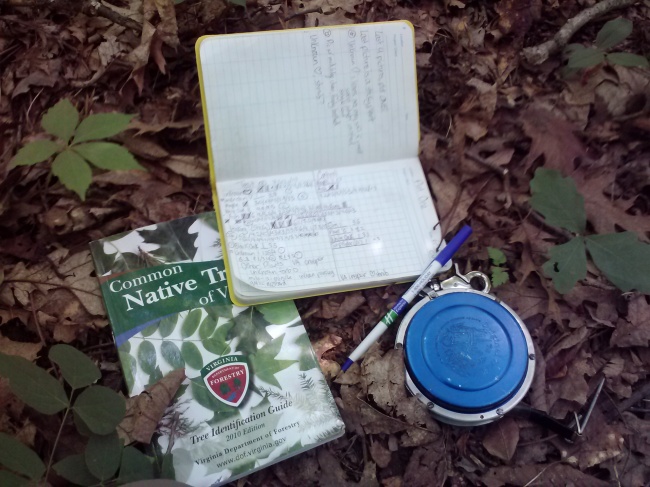

In order to collect the ticks, we drag a white sheet along the forest floor. Excited by the prospect of finding a host, ticks latch onto the fabric just as they would grab onto a hiker’s pants. Once we travel fifteen meters we flip the cloth over and methodically search for the infectious hitchhikers.

We search along the edges of trails where tourists are most likely to encounter these pests

We search along the edges of trails where tourists are most likely to encounter these pests

This process is made more difficult by the ridiculously small size of these creatures. Grown ticks are fairly easy to detect, but most of what we find are in their larval or nymph stages and are only as big as a speck of dirt. To my dismay, after the very first flip our sheet was covered in thousands of specks of tick-sized dirt. Hunting ticks, it turns out, is an I-Spy game.

Our white sheet got dirty. Who could have predicted that?

Our white sheet got dirty. Who could have predicted that?

When we find a tick, we can identify its species based off of its body shape and color. Deer ticks are very dark and teardrop shaped, whereas others are lighter and rounder. Once we have an ID, we wrangle the tiny monster into a vial with a toxic alcohol solution that kills and preserves the specimen.

This spider is ENORMOUS compared to the ticks we found

This spider is ENORMOUS compared to the ticks we found

If you’d like to see tick-hunting in action, check out this footage from the field!: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MYlJ3yJCjcQ